Not the men they might have been

Just before Tarek Lubani and John Greyson returned to Canada from their 50 days of captivity in Egypt last October, the coverage of the incident reached a sensational peak in the Toronto media. Ezra Levant of the Toronto Sun red-baited the two Canadians as they lay captive in Cairo, calling them left-wing attention seekers, professional agitators – that is, blaming them for their own predicament. In the Globe and Mail, Margaret Wente went a step further, outing Greyson as a gay activist in her column.

Hearing this mix of names, place and actions – Cairo, rising Arab nationalism, Gaza, Canadians imperilled in Egypt, External Affairs, personal attacks in the media, with an undercurrent of homophobia – dumped me into a time machine and whisked me back to an infamous moment in April 1957. It was a far bigger storm, involving my uncle, Arthur R. Kilgour, who was stationed in Cairo. (My parents gave me his name when I was born a year later.)

The story involves several wars. Depression. Student idealism. Fascism. House arrest. Accusations of espionage. The Cold War. Reputations destroyed, careers finished. Interrogations, brainwashing, and even death in police hands.

And also … the possibility of a deeper force at work. Homophobia. Along with deception, fear, secrets. Cyanide and suicide.

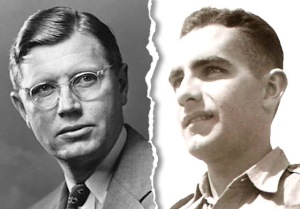

Herbert Norman’s 1957 suicide caused a wave of protest in Canada, later replaced by accusations that he was a Soviet spy

At the centre of it is the abrupt, violent death of Egerton Herbert Norman, the Canadian ambassador to Egypt and my uncle’s immediate superior, who died on a Cairo sidewalk after jumping from a nine-story apartment building. His suicide raised an international controversy because of U.S. involvement (see image at right; click to enlarge), and it began a historical debate that would rage on and off for almost six decades, until 2010, when the last of the RCMP records about the Norman case were declassified. (Most of the CIA files on Herbert Norman are still held in secret.)

Finally, it involves an uncle whom I resembled, and who I also loved and admired. He influenced me at a vulnerable time, but he also later showed a streak of intolerance that I could never square with his Christian beliefs. He died the same week I lost my father, in 2000, and sometimes the two of them merge in my consciousness, because of their similar temperaments and dark looks – and also their connection to the mysteries and secrets of a fearful, earlier era.

Shaped by depression and war

My uncle was born in 1919, ten years after Herbert Norman. The two of them followed career paths that were hugely influenced by world events and their small place in a larger political context. Norman was born and raised in Japan, the son of Canadian Methodist missionaries. He grew into a tall, fair-haired man, outgoing and intelligent, although physically weak (because of tuberculosis as a child) and perhaps prone to depression. He studied classics and medieval history at U of T, then European history at Cambridge, England and finally Japanese history at Harvard, before entering the diplomatic corps in 1939, shortly after earning his PhD and marrying his college sweetheart.

My uncle Arthur grew up in Toronto, also studied classics at U of T, earning his BA before going overseas to fight in WWII. After the war, he completed his MA in Toronto, then entered the diplomatic service in the early 1950s, a decade after Norman. He was short and slim, with dark hair, olive skin, and deep-set, penetrating blue eyes under a thick set of black eyebrows. His normally quiet and gentle demeanor would sometimes reverse itself into sharp observations, forcefully argued. He loved history, art, architecture and classical music. He never married.

Norman’s upbringing was religious and progressive while my uncle’s was religious and conservative. The cauldron of the 1930s depression radicalized Norman, and even turned him away from Christianity. At university he became an intellectual Marxist, and associated with student communists at both Cambridge and Harvard.

By contrast, my uncle Art was shielded from the Depression by his well-to-do Toronto family, but as a student in the 1940s he was persuaded to vote CCF (predecessor to the NDP), something that might have troubled his father, a successful Toronto businessman and car dealer.

Norman’s first Canadian foreign service job, as a language interpreter in Japan, coincided with the outbreak of WWII in Europe in 1939. When Japan bombed Pearl Harbour in 1941, it too was suddenly at war. Norman and the rest of the Canadian legation were placed under house arrest in Tokyo for almost a year by the Japanese authorities, finally returning to Ottawa in a prisoner exchange.

After the war ended in 1945, External Affairs sent Norman back to Japan, where his familiarity with the society and language was a huge asset. He worked for the international occupation government that ran the country for seven years following its war defeat, led by U.S. General Douglas MacArthur.

Norman’s doctoral thesis on the emergence of Japan as a modern nation became a blueprint that was admired by westerners and Japanese intellectuals alike. He was General MacArthur’s assistant in the occupation government, and helped write the new Japanese constitution. His star rose quickly in the five years he spent there.

By his late 30s, he wasn’t only studying history as he had been trained to do, he was making it.

But, the world’s political stage was changing rapidly, first as a result of Russia exploding a test nuclear weapon in 1949 (four years after the U.S. had dropped a real one on Japan), then, in 1950, with the victory of the Chinese Revolution and the ascension of communism in Asia. The Cold War had begun, a geopolitical era that would dominate for almost four decades.

Most political debates, and many careers, would get reduced to simple black and white allegations, even when the reality was far more complex and historical. Are you for the West, or against? Were you ever a communist, or a sympathizer, even decades earlier, during the capitalist breakdown of the 1930s?

That was Herbert Norman’s predicament. His rather passive and academic student radicalism earned him the suspicion and then enmity of the U.S. – not so much his immediate supervisors in Japan, who admired his diplomatic gifts, but amongst U.S. politicians. As the western foreign policy objective in Japan went from pro-democracy (immediately following the war) to anti-communism (in the late 1940s), Norman became a target, particularly as the McCarthy era unfolded in Washington. His name was raised before a U.S. Senate committee, with accusations that he was a spy for the Russians, and the charges were repeated in the news media.

Eventually, Norman was recalled from Japan in 1950 by the Canadian government, and given a six-week interrogation by the RCMP in Ottawa about his 1930s political associations. His answers satisfied his boss, External Affairs Minister Lester Pearson, however, after a short stint with the department in Ottawa, Norman was sent far away, to New Zealand, where the U.S. could not object. The whole experience scarred him deeply.

Encounter in Cairo

Following his service in the Canadian Army, and then the completion of his post-graduate studies, my uncle Arthur also entered the foreign service. His career began in Paris, followed by a posting in the early 1950s to what was then called Indochina, soon to be Vietnam.

I have little evidence about what he did or thought during those years. But he would have witnessed the same political transformations as Norman, because Vietnam’s emergence from French colonialism after 1945 was also moulded by the Cold War. In fact, Arthur Kilgour was closer to the real action than Norman, with the U.S. and Russia backing opposite sides during the first Indochina war that stretched until 1954 and saw the country divided into North and South (setting the stage for the better-known Vietnam war in the 1960s).

Norman was recalled from New Zealand in the spring of 1956 and by August was posted to Cairo as the new Canadian ambassador. If Pearson was hoping to keep him out of the limelight, he couldn’t have chosen a worse place than Cairo. A brief but major international crisis unfolded shortly after Norman’s arrival, involving all the world’s superpowers, with heavy Cold War overtones.

In July 1956 Egyptian President Gamel Abdel Nasser seized the internationally-run Suez Canal, as part of his campaign for national independence. Regulation of shipping through the canal – the major shipping route between Europe and Asia, and the primary conduit for Middle East oil – was threatened. This prompted an invasion by paratroopers from Britain, France and Israel, and the aerial bombing of Cairo.

Both the U.S. and Canada favoured de-escalation of the crisis and the withdrawal of foreign troops. Canada’s External Affairs Minister Lester Pearson floated a novel idea: have a United Nations peacekeeping force supervise the foreign withdrawal from Egypt and the re-opening of the canal.

One of the diplomats appointed to negotiate with Nasser for the west was Canadian ambassador Herbert Norman. His quick grasp of Arab politics and his sympathy towards Egypt’s post-colonial aspirations won Nasser’s trust and agreement, and the Egyptian president assented to U.N. peacekeepers, including a large contingent of Canadian soldiers.

As Canada’s role in Egypt expanded, so too did its embassy staff. One of the new recruits, in February 1957, was Arthur Kilgour, who was hired as Herbert Norman’s Principal Secretary. He was put in charge of press relations and organization of Norman’s calendar. In a 1984 memoir, Arthur Kilgour wrote glowingly of his initial encounter with Norman: “There was no pretence about Herbert Norman. Devoted to the diplomatic service, he was a diplomat’s diplomat.”

Eight months after it began, the confrontation was over, as foreign troops withdrew from the country. Pearson would win the Nobel Peace Prize that year for his ingenious solution, and Canada’s role as a middle power in world diplomacy was born. (Seven years later, Pearson would become Canada’s 14th prime minister.) Quite an accomplishment for Norman’s first half-year as a full-fledged ambassador!

But a dark cloud was descending on the Canadian embassy in Cairo. Norman’s old foes in the U.S. Senate could not abide his close involvement in yet another Cold War conflict (Egypt was developing ties to the Soviet Union and had recognized the newly communist China, both of which angered the U.S.). The earlier accusations that Norman was a communist mole, either passing secrets or carrying out Moscow’s orders, were made again before the Senate Internal Security Sub-Committee in Washington, in mid-March 1957.

Pearson re-acted angrily in a statement before the House of Commons, saying Norman had been cleared of any suspicion five years earlier, and defending Canada’s right to appoint its own representatives without foreign intervention. But could Pearson resist the political pressures in Washington? Or would he have to recall Norman again, in order to appease the American legislators?

On the morning of April 4, 1957, Norman took matters into his own hands. He penned five separate notes to his wife, family, friends and employer, then took a short walk from his residence to the apartment building where his friend the Swedish ambassador lived. He rode the elevator to the eighth floor, then walked an additional flight of stairs up to the roof of the building, one of the tallest in the city at the time. There, he removed his jacket, glasses, cuff links and watch, spent perhaps 10 minutes contemplating his decision, observed by witnesses below and a window cleaner on the building opposite.

At about 9:00 am, he climbed the roof’s parapet, then leapt abruptly into the air, fell rapidly for 100 feet, bounced off a Swedish official car, and died immediately as he crashed to the sidewalk, his skull, torso and limbs fractured to pieces. His death was witnessed by an Egyptian friend, Abdul Malik, who lived in the same building, and by his personal driver, Costa, who had been sent by his wife to look for him.

Searching for an answer

My uncle Arthur was in the embassy that morning, awaiting Norman’s arrival so they could proceed with the usual planning of the day’s agenda. But he was receiving confusing signals. Norman’s wife was calling to ask for his whereabouts. Meanwhile, there was a police report about a suicide near a familiar downtown apartment building, around the corner from Norman’s residence. Arthur Kilgour put all the pieces together, and rushed out, fearing the worst. It was confirmed when he reached the building, finding the Cairo police clustered around the mutilated body of his director.

The impact on my uncle and the embassy staff (and of course, Norman’s wife Irene) was “shattering”, in my uncle’s words. His immediate tasks were to convey news of the tragedy to her, then to the embassy, and then on to the Canadian government in Ottawa. He also became Canada’s chargé d’affaires, their lead diplomat in Egypt.

He had to liaise with the Cairo police, deciding with them whether there would be an autopsy (there wasn’t), interpret the hurried scrawl in various notes Norman left behind, then answer the questions being raised by the Cairo and Canadian news media. Finally, he had to reconstruct the last two weeks of Norman’s life in an 11-page report to External Affairs, and attempt to provide an explanation for such a shocking turn of events.

The “what” of Norman’s death seemed clear enough. Because of several witnesses, above and below, no one doubted suicide; there was no serious question of foul play. But the question of “why” would endure, quite literally, for more than half a century.

Norman’s own explanation in his longest suicide note, an unaddressed letter left at his residence, and in shorter notes to his siblings and his wife, was not all that complicated. He cited the Washington persecution that had returned two weeks earlier, and which he feared would dog him for the rest of his career. He felt he could never provide an answer that would be sufficient for those who questioned his loyalty to his country and his friends.

“Time and the record will show to any who is impartial … that I am innocent on the central issue,” Norman wrote, perhaps on the morning of his suicide. “I have never conspired or committed an act against the security of our state or of another state. Never have I violated my oath of secrecy.”

To his wife Irene, Norman wrote more poignantly: “Dearest and purest and kindest. I am not fit to live. I am not fit to kiss your feet. You are in a world apart, so pure and merciful and compassionate. I cannot live with myself any more. I am without hope or deserving any sympathy.”

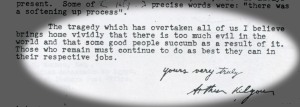

The conclusion to Arthur Kilgour’s report to External Affairs: “There is too much evil in the world.”

My uncle’s report to External Affairs described the anguish of Norman’s last two weeks, as his mental health deteriorated in the wake of the new Washington Senate allegations. He could not work properly. He slept on the couch in his office. He was detached in social situations. Finally, he consulted his Cairo doctor, who prescribed anti-depressants.

Everyone, including my uncle, assured Norman that the fresh charges would not last, but the ambassador voiced his doubts on that score. Finally, on the night before his suicide, he attended a movie opening with his wife, two other friends and my uncle Arthur. Quite by chance, “The Mask of Destiny” was a Japanese film, which Norman would have understood without subtitles. It featured a protagonist prince who wants to escape his royal destiny by wearing the mask of a commoner. The night the mask is delivered, the prince is murdered – it has foretold his destiny, his death as the victim of intrigue.

Could Norman have seen anything of his own predicament in the film? My uncle doubted that the event was any sort of trigger for Norman’s suicide. He pointed instead to the pressures the ambassador was facing over the Suez crisis, the difficulties and brutalities that came with living in Cairo, and the anguish that the new Washington allegations were causing him.

“Mr. Norman felt that he had let the Canadian government down because it previously had said that he had never been a communist,” my uncle wrote in his report. “But now he was afraid that a committee in Washington might show that he had almost been a communist.”

Most surprisingly, Norman’s suicide was not a complete surprise to those who knew him best, even if it was a shock. He had discussed his suicidal thoughts with his wife and his doctor two days before his death. They had all agreed upon a plan that included sedatives for Norman and an extended vacation in Spain. Part of the reason for viewing the film on April 3 was to keep Norman occupied and in touch with others. When he left Norman that night, Arthur Kilgour says the ambassador “appeared relaxed and composed.” The next morning, he jumped to his death.

Reaction at home in Canada was swift. In the House of Commons, NDP Member of Parliament Alastair Stewart called the suicide “murder by slander.” Pearson mourned the loss of a friend and an invaluable public servant. He had in fact written to Norman in late March, expressing his full support, but the Cairo embassy was without a teletype machine – his letter was sent by regular mail, and never reached Norman before his suicide on April 4.

According to an interview that historian Roger Bowen conducted with Irene Norman in 1983, “Herbert killed himself in order to protect his mentor in External Affairs, Lester Pearson.” The minister had not been fully open about Norman’s student communist past when he defended him before the House of Commons in 1950, and the diplomat feared the renewed allegations would damage Pearson politically, and undermine the peacekeeping process in Egypt.

Was he or wasn’t he?

But a counter-explanation was brewing – that Norman’s death was a cover-up for his own nefarious actions – that it was, in a sense, proof of the allegations against him. His suicide, as the argument went, prevented him from having to implicate friends or admit the espionage he’d been conducting for the previous two decades since his student days at Harvard. He wasn’t just a student radical, but rather a current Soviet spy representing western interests at the highest levels of world diplomacy in Japan, and then Egypt.

Does that seems far-fetched? Not in the climate of the 1950s. And that pall of anti-communism hung over the case for decades. (We learned three years ago, through declassified RCMP documents, that the Canadian police interviewed Irene Norman in 1969, 12 years after his death, still looking to prove the allegations of spying. In other words, Norman was persecuted on both sides of the border. He was not wrong in suspecting that his tormentors would never give up.)

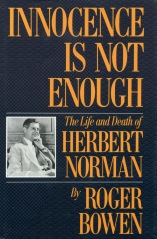

In the late 1980s, two books were published about the Norman case, one arguing in his defense, by political scientist Roger W. Bowen (“Innocence is Not Enough”), the other a character attack by U of T political science professor James Barros (“No Sense of Evil”), which alleged more than had even been ventured by the hawkish U.S. senators in the 1950s.

Finally, in 1990, the Canadian government commissioned its own investigation. It turned over the RCMP’s files on Norman’s case (then held by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service) to history professor Peyton Lyon, and asked for his assessment.

The result? A thorough repudiation of the allegations, and a confirmation of Norman’s initial testimony to the RCMP in the early 1950s:

- that he was an intellectual Marxist at Cambridge and Harvard, and had associations and friendships with communist party members at the universities, but

- that he was not a communist party member himself, and

- that he never betrayed his oaths of secrecy and loyalty to his country in the years that followed.

Lyon’s report answered the espionage allegations against Norman (especially those levied in the Barros book) point by point, and suggested that the best explanations for his suicide were the ones he himself provided in his suicide notes: a mental breakdown, perhaps depression, brought on by the dilemma he found himself in, and possibly exacerbated by being thrust into such an international pressure-cooker without much prior experience at that level of conflict.

In 1999, the NFB released a fascinating 100-minute docudrama titled “The Man Who Might Have Been.” Shown on CBC television the next year, it told Norman’s story in popular terms, with re-creations played by actor Greg Ellwand, since there was no film record of Norman. It concludes with a shot of “Norman” climbing to the roof of the actual Wadi El-Nil building in Cairo, which still stands, then calmly and silently removing his glasses and jewelry. You can’t help but despair at the tragic outcome you know is to follow, even though the film does not attempt to recreate it.

Finally, by 2010, the CSIS files on Norman were released to the Canadian public and news media. Just as Prof. Peyton Lyon had reported 20 years earlier, there was no smoking gun, no evidence to suggest that Norman was anything other than who he said he was, a conscientious diplomat with, at most, a radical student past 20 years earlier.

(Norman’s wife Irene lived until 2003, her 94th year, exactly twice the duration of her husband’s life. She returned to Canada, and had careers as a dietician and in real estate. Her obituary said she was a “cynical optimist” who loved music, gardening, reading, cooking and social justice.)

The aftermath for Arthur

So what became of my uncle Arthur Kilgour? What impact did the Norman case have on him?

I don’t have a lot to go on, just my memory of stories told by two of his siblings, my father R. Govan Kilgour and my aunt Ruth Turriff, who themselves scarcely understood the mysterious incident. And I have my own memories of a distant but intriguing uncle, who I got to know better in my early 20s.

Following the crisis of Norman’s suicide, Arthur was Ottawa’s lead man in Egypt. But that didn’t last long. By 1958, he was recalled to Ottawa and a new ambassador was put in charge. Even though Arthur Kilgour had no radical past, and had no friends who had been communists in the 1930s, it seems he was nonetheless tainted by his proximity to Herbert Norman. As well, he contracted sleeping sickness in Egypt, a parasitic African disease that wreaks havoc on the central nervous system. He had to return to Toronto for treatment, and he never worked for External Affairs again.

I don’t know if he resigned, or was pressured to leave. But his chosen post-war career, which had lasted but a decade, was over.

From here, the story takes an even more sinister turn, even though precise facts are hard to come by. My uncle also had a mental health crisis following his Egyptian experience. He told Norman’s biographer, who interviewed him in the mid-1980s, that he’d suffered a “nervous breakdown.” According to my aunt Ruth, Arthur was sent to Montreal for treatment at a psychiatric facility of some sort.

I cringed when she told me this.

I’d just read “In the Sleep Room” by Anne Collins, a 1988 exposé about how the Canadian government allowed the CIA to experiment with brainwashing and LSD, using vulnerable Canadian patients as guinea pigs. The location was Montreal, the time, late 1950s and early ’60s. Silently, I asked myself, “WTF? My uncle Arthur was possibly involved in that horror?”

I asked for more details, but she couldn’t provide them. Arthur had never been candid with his siblings about that period of his life, or the effect it had on him. All she knew was that he disappeared for awhile after Cairo, re-emerging in Toronto as a somewhat changed man. He built a new domestic life for himself in the city. He was hired as the University of Toronto’s assistant registrar; by 1965 he was its Director of Admissions. Throughout the decade, he lived alone in a Toronto apartment.

Me and my uncle

I first encountered my uncle Arthur when I was young child in the 1960s, taking summer holiday visits east to visit my dad’s family. He was my namesake uncle with the asymmetric smile, a cleft chin, and a wicked sense of practical humour. He wasn’t so comfortable with children, having none himself. When I see him in my father’s home movies, he looks a little harsh, even physically rough with his nieces and nephews. But I felt no malevolence from him whatsoever. I remember his underlying aesthetic and intelligence, and I liked it.

In 1969, with less than a decade under his belt in Toronto, my uncle’s life again took an abrupt turn. He retired from public life altogether, buying a farm near Peterborough with funds he’d inherited from his parents, building an atypical and architecturally stunning modern house overlooking the hills of Cavan Township. There, he retreated to his books and music. He was just 50 years old. His sister, referred to him as a “recluse”, but that wasn’t really true. He was active in his local church, and eventually won election to Cavan council – a former international diplomat, now engaged in matters of rural policy and development. I thought it was rather cool.

Arthur Kilgour retired to a rural property near Peterborough, in a house designed by architect Ron Thom

In 1978, I was contemplating university myself and had been accepted to both U of T and to Trent University in Peterborough. I had more or less decided on Toronto when I cycled up to see my uncle Arthur, the first time I had ever visited him as an adult, without the supervisory presence of my parents or other relatives.

He showed me his house, vegetable garden and pond with Canada geese, then offered to take me up to Trent for a tour, with introductions to professors that he knew. I was immediately impressed by the newish university, almost the polar opposite of U of T in both size and appearance. Its main campus was designed by acclaimed architect Ron Thom, the same man who had designed my uncle’s new home. Trent was spread out at the foot of a wooded drumlin well north of the city, with the Otonabee River bisecting the campus and a graceful concrete footbridge linking the two banks. “Oxford on the Otonabee” was the popular term for its English-referenced modern design.

I was surprised that Arthur was favouring this modest undergraduate institution over his own alma mater and recent employer. Later, I would wonder why he recommended a university with a definite left-wing reputation, when his own political views had moved steadily to the right.

Never mind, the little university won my heart immediately. I began my studies there two months later. Although Trent was a better match for me than U of T, I was also comforted by the knowledge that my uncle wasn’t far away, and was offering support. My own home and parents were far away in Vancouver.

Political differences

I spent five years in Peterborough, studying Canadian history and politics. But I became almost immediately involved with a campus student organization that was active around environmental and peace issues. And in my second year I began writing for the student newspaper, which was coincidentally named … The Arthur. (No relation, to either of us!) As my extra-curricular activities increased, my course load dropped. By 1982, I was the full-time newspaper editor, with a six-day, $100-per-week job, fully engaged in university politics as an observer, and sometimes an actor.

I saw my uncle Arthur less and less. When I did, he was noticeably cooler towards me. I knew he was keeping tabs on my activities and writing, perhaps through his campus friends. When we spoke, he would question me closely about my activism and my newspaper work.

Two political issues dominated my year as editor, besides the routine coverage about university and student issues: apartheid in South Africa, and cruise missile testing in Canada. Although the apartheid regime was facing international sanctions because of its racist internal policies, it still attracted foreign investment, including support from Canadian banks and mining companies. Students were urging the university to withdraw any funds it had invested in the country through its pension plans.

At the same time, my uncle Arthur was on a study tour of South Africa, visiting the bantustans, the “homelands” offered by the apartheid government as a separate, quasi independent economic and political home for its black population. It was the apartheid government’s attempt to short-circuit rising black nationalism into a “separate but equal” political solution.

Arthur returned from his church-sponsored tour of the country and wrote favourably in the Peterborough newspaper about the homelands policy. At almost the same moment, I was speaking to the university’s Board of Governors, asking them to re-consider their investments and questioning the legitimacy of the CIBC representative who sat on Trent’s board. We were on complete opposite sides of the same issue, each aware of the other’s activity.

Closer to home, in Toronto, Litton Systems was building the guidance system for a new U.S. weapon, the cruise missile. And the local peace group, whose office was beside our student newspaper in downtown Peterborough, was leading non-violent protests at the Etobicoke plant. When Litton became the target of a terrorist bombing in 1982, all eyes and police attention turned to peace movement activists, including our friends next door. One of them was arrested by police and taken to a jail in Toronto, to be held without charges, and the peace group’s offices were raided by the local police.

The next evening, as I was writing the dramatic story for that week’s paper, I received a phone call from my uncle.

“You better be careful what you’re doing there,” he said in a accusatory voice. I asked what he was referring to. He ignored my question and replied, “you’ll never get a job with the Canadian government if you continue your activity.”

Although I wasn’t so naïve to the possibility that maybe our offices or phone were being monitored, I had no idea about the past that he was referring to. I knew nothing about Herbert Norman, or the fact that this man’s political past had somehow contributed to the take-down of my own uncle’s career.

Shortly after that, I began referring to myself as Art Kilgour, so his friends would not confuse my byline with his, and vice versa.

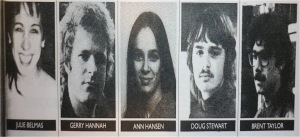

The Squamish 5, arrested in 1983 for conspiracy to rob a Brinks truck. Taylor and Hannah later pled guilty to the Litton bombing

After university, I moved back to Vancouver. Earlier that year, five young people were arrested near Squamish B.C. and charged with conspiracy to rob a Brinks truck. Had they been framed, I wondered? So I attended the opening day of their trial in New Westminster, and immediately realized that the wiretap evidence against them was damning. It was also clear that they’d been responsible for the Litton bombing, the firebombing of several Vancouver porn video stores, and were planning to rob an armoured car in order to finance their brand of activism.

It wasn’t peace movement members that bombed Litton, it was members of a Vancouver cell who had crossed a distinct line that separates peaceful from violent protest. Their political ideology was not communist but rather anarchist. They had nothing to do with the Soviet Union or spying. Their path to urban terrorism isolated them from the activist community they hoped to inspire, and brought it much discredit. Two of the five pled guilty to the charges; the other three were sent to prison upon conviction.

Is this the sort of association my uncle had been warning me against? If so, he needn’t have worried. I was repulsed and even disillusioned by it. After returning to Toronto, I worked voluntarily with an El Salvador solidarity group, producing a newspaper called El Salvador Libre. My Canadian pals at the paper included a CBC radio journalist, a Toronto Star reporter, and a young videographer named John Greyson. We worked together for about two years, right in the middle of a period when death squads and human rights violations were at their height in the tiny Central American country.

Revising the Norman case

I saw little of my uncle Arthur over the next 15 years, other than at large family events like my grandmother’s 100th birthday party in 1993. Occasionally, his name would surface in the media. He reviewed the two 1987 books about Norman’s death for Maclean’s magazine, and he favoured the Barros interpretation (that’s the one with this sub-title: “The strange true story of the Cold War diplomat who committed suicide after being exposed as a Soviet spy”).

How could my uncle write so unfavourably about the man he had served under in Egypt and for whom he had earlier expressed such admiration? His 1957 report to External Affairs was a nuanced psychological portrait of a man under stress and persecution. What had caused his shift to endorsement of the old Cold War accusations?

A few years later, after Prof. Peyton Lyon’s report to the federal government (the one that cleared Norman’s name for good), my uncle revised his thesis in a Globe and Mail op-ed piece. Now he seemed to blame Norman’s humanist philosophy, which left him without a moral rudder in the turbulent waters of Cairo.

“It is not unfair to say that (Norman’s) crisis was essentially of his own making,” my uncle argued, “due to naïveté and past indiscretions.” Essentially, he was arguing that if Norman hadn’t abandoned his Christian faith in the 1930s, he would have had something to turn to when he faced the confusion of the Egyptian crisis.

“If he had perceived that what was happening to him was a time of testing, that in confronting difficulties life can become meaningful, and that what he was experiencing could provide the avenue to extricate himself from the prison of a false ego, he might have survived the circumstances.”

I may admire the cogency of my uncle Arthur’s writing there. But I think he puts the blame back on Norman, rather than the extraordinary circumstances he faced. My uncle guessed badly at how history would soon unfold in South Africa, and his Cold War thinking was still influencing his view of the Norman crisis, even after the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall.

I recently interviewed Roger Bowen, Norman’s sympathetic biographer. He still follows the case, and is hoping the CIA will soon release the 66 documents it has about that period of history, so that the full truth of the U.S. role can be known.

Bowen says that my uncle floated the same theory with him about Norman’s crisis of faith. “I had the impression,” says Bowen, “that Arthur was talking more about himself than about Norman – that he’d had his own crisis of faith in Egypt, and was transferring the feelings to Norman.”

Bowen also recalls my uncle Arthur as a gentle and intelligent man. He concludes, “In Egypt, he was just in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Whatever the case – and again I have very little to base my conclusions on, not even a reliable chronology of my uncle’s life between 1955 and 1965 – I believe there’s no doubt that the Egyptian crisis was central to understanding my uncle’s abrupt turn away from a promising career in External Affairs to early retirement just a decade later.

Mixing up his Arthurs

My uncle’s health declined through the 1990s, and he moved from his farm to a ground-floor condo in Peterborough, quite close to the university. He had a circle of friends and neighbours in Peterborough, but saw little of his immediate family, just an hour away in Toronto. I also saw him quite rarely, as my life got taken over by babies, career, mortgages and moves. I once attended a family event at a Toronto restaurant, and I arrived underdressed for the formal venue. Never mind, my uncle Arthur had a spare sports coat in his car, and it fit perfectly.

Although my uncle was clearly unwell by 2000, my bigger concern was my own father in Vancouver, who was having disabling, small strokes. I flew west several times that year. On one visit in late spring, I was lunching with Dad at his small table when he became muddled about my identity. He thought I was his brother Arthur, instead of his son. He quizzed me about “my” upbringing and early homes in Toronto. When I couldn’t convince him that I was his western-born-and-raised son, I suggested it was time for his nap.

When I went into his bedroom 10 minutes later, he had an old photo album spread out, and was pointing to a shot of two boys on either end of a homemade banner that read “Welcome Home.” I didn’t recognize the faces so I asked what the photo was about.

“That’s you and Bob,” (his eldest brother) my father said. “You made that sign to welcome mother and me home from the hospital after I was born.”

“Yes, of course I did,” I assured him. “I was your big brother after all!” At that, Dad relaxed and went to bed.

Arthur G. Kilgour (left), my uncle Arthur R. Kilgour (right), and my father R. Govan Kilgour (front)

We know little about my uncle Arthur’s final day. He died of a heart attack in the corridor of Peterborough General Hospital, awaiting treatment for … we’re not sure what. There was no autopsy. His neighbours helped organize a memorial service, but could provide no answers. I was in Vancouver, where Dad was in a nursing home, in the final stages of dehydration because his strokes had destroyed his ability to swallow, and he opted not to be transferred to a hospital.

When I told him that his brother Arthur had died he nodded and blinked his eyes slowly, even though he could not talk. A few days after his brother’s death, Dad also slipped away, with very little medication and no heroic medical interventions. I flew from one memorial service in Ontario for my uncle to another one two days later in Vancouver for my father, the two events merged into one in my memory.

The homophobia subtext

But that’s not the end of the story. After Arthur’s death, I became more interested in the Norman case. I read the major books, researched newspaper accounts, and even received some of my uncle’s private files after his estate was settled.

And then I learned of a 1993 play by novelist and playwright Timothy Findley, called “The Stillborn Lover.” It’s a convoluted drama that didn’t earn much critical acclaim, even as Findley’s novels won him praise and awards. But the play’s central character, Harry Raymond, is a Canadian diplomatic who is recalled to Ottawa in the 1950s amidst suspicions that he’s homosexual, which he admits to his daughter in the course of the drama. (Where did Findley get the name? He probably invented it, but the U.S. ambassador to Egypt during the Suez Crisis was named Raymond Hare, perhaps a coincidence.)

Apparently, the Raymond character is Findley’s fictitious way of discussing the lives of two real diplomats: yes, Herbert Norman, and also John Watkins, the Canadian ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1954–56, and a friend of Norman’s. In 1964 Watkins was secretly detained by the RCMP and the CIA in Montreal and interrogated, about allegations that he was a communist, and also homosexual.

Watkins died several days into the questioning, with the coverup story and obituary saying that he had suffered a heart attack while out with friends. After the Quebec government’s intervention, the RCMP eventually admitted that he had died in a Montreal hotel room during his interrogation.

Another promising Canadian diplomat in the same era, John Wendell Holmes, served in various capacities from 1947 to 1953, with postings to the Soviet Union and the United Nations. At that point, he was recalled to Ottawa, apparently because his bachelorhood led External Affairs to believe he was a possible homosexual, and therefore a security risk.

I have no way of knowing whether Findley’s dramatization was simply the imagination of a Jung-influenced writer (who was openly gay). In his book “Love, Hate and Fear in Canada’s Cold War,” Richard Cavell analyses the play and speculates about Herbert Norman and the generalized climate of homophobia in the 1950s, but he provides scant details.

Although Findley may have had to imagine the particulars, he is surely right about a more general point: when you combine communist witch-hunts with the threat of deeper, more personal secrets, then the psychological pressure on the accused mounts enormously, regardless of whether the allegations are true or not.

If you can’t quite believe this, or think it sounds like conspiracy theory, then here’s an astounding example from the U.K., with a recent twist.

Just last month, British PM Gordon Brown issued a posthumous apology to Alan Turing, the Cambridge mathematician who broke the German Enigma code during WWII, contributing hugely to the eventual Nazi defeat.

Apologize? Why?

Because in 1952 the war hero was prosecuted for gross indecency after admitting to a homosexual encounter, which was against the law. He was chemically castrated as punishment, and stripped of his government job. He killed himself two years later, by eating an apple laced with cyanide. A feature film about Turing’s life is currently in production in the U.K.

That’s how persecution worked in the 1950s, and not just in the U.S. Being outed or even accused of homosexuality was perhaps a worse outcome than being called a communist.

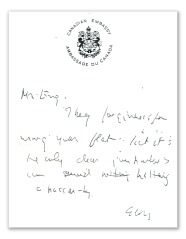

One of Norman’s suicide notes, an apology to his friend Brynolf Eng, the Swedish ambassador to Egypt

Roger Bowen writes that, “One of several suicide notes leaked to the press [following Norman’s death] seemed to imply that Mr. Norman had had a close, perhaps homosexual, relationship with the Swedish ambassador to Egypt, Brynolf Eng.” It was indeed from Eng’s building that Norman jumped to his death. But the press quote was exagerated. The real note (at right) said simply, “Mr. Eng, I beg forgiveness for using your flat. But it is the only clear jump where I can avoid hitting a passerby. – E. H. N.”

Anthony Blunt, a U.K. art historian who was convicted in 1979 of spying for the Soviets from the 1930s to the 1950s, is alleged to have told British journalist Chapman Pincher that, “Herb [Norman] was one of ‘us’ … meaning a recruit to Soviet Intelligence and not just a homosexual.” (Blunt and Norman were both at Cambridge in 1932–35, and moved in similar circles.)

In his Norman biography, Bowen discounts the homosexual allegation because there is no evidence showing this to be the case. In this context, it sounds more like homosexuality was just another charge that Norman’s detractors were trying to pin on him. (There were also allegations that Norman had a heterosexual affair in the 1940s with a Japanese woman, again, not publicly confirmed or proven.)

The basic facts are this: Norman married during his graduate student days. He and Irene Norman had no children (which Bowen attributes to Herbert Norman’s egocentricity and total immersion in his work, and the breakdown of physical attraction between them). He was characterized as “sensitive” by many who knew him, including my uncle. A major turning point in his life was the loss of his close Cambridge friend John Cornford, a British Communist Party member who died fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Norman wrote of his anguish at the loss, and the fact that he “loved” Cornford.

But speculating on Norman’s sexuality now seems as futile as extrapolating his political philosophy from friendships he made when he was a student in the 1930s. And maybe it doesn’t much matter if Norman was homosexual or not. Having the rumours circulate was a threat to him either way.

And what of my uncle? It seems quite possible that his recall by External Affairs after Norman’s suicide had as much to do with his bachelorhood and the questions it raised, as any suspicion that he aided Norman, the Soviet spy.

A few years after my uncle’s death, a cousin of my mother’s, John Greene, visited me in Elora. He was exactly Arthur’s generation, same era, same home city. But instead of the diplomatic service and academia, his circle was artistic. He was a painter, both commercial illustration and fine art. And he socialized with a crowd where homosexuality was, at least to some degree, accepted or acknowledged.

I asked him about the Herbert Norman case, but he had little to say. Then we discussed my own father’s homosexuality, something he said he knew about at the time of my parent’s marriage in 1956. If so, I asked, why he hadn’t mentioned it to his cousin, my mother, who was about to make an unfortunate life choice?

He just shrugged, replying, “Homosexuals got married back then, they had to.”

So what of Arthur R. Kilgour? What did John Greene’s artistic gay-dar have to say about my uncle, with whom he crossed paths several times in the ’50s and ’60s? Before replying, John hesitated, looking down at the grass by the river where we sat. Then he looked me straight in the eye and replied: “Your uncle Arthur was gay, definitely.”

My head swirled. This was just one person, alleging something that could never be demonstrated or proven. I went to my aunt Ruth, Arthur’s sister, and asked her if this seemed plausible. She doubted it. He was “asexual” according to her. But to me, that meant he was so private with regard to his sexuality (never dating anyone of either sex, and mostly living far from his family’s view) that she didn’t consider it a relevant issue.

The what-ifs

So I’m left with very little in terms of facts. I can only pose, “what-ifs”, then think it through. If Norman, or my uncle, had been homosexual (or if Norman lived some sort of hidden heterosexual life apart from his wife), then it would have added another, complex layer to the whole case. And it would explain at least two things.

Firstly, it would shed further light on the depth of Norman’s anguish, which no-one seems to comprehend fully, then or now. If he feared the revelation of a secret far more personal than the spying allegations, could this have driven him to the roof of the Cairo apartment building? That’s speculative, but I think it jives rather well with Norman’s suicide note handwringing about his Christian failings (to his devout brother) and his unworthiness towards his wife (“I am not fit to kiss your feet”).

Secondly, it might help explain my uncle’s initial sympathy towards Norman, and his later condemnation. I know my uncle disapproved of my father’s homosexuality, which he only learned of quite late in life. Arthur judged his brother (who was a former United Church minister) in religious terms, and it hurt my dad deeply. I think Dad loved his brother, and would have liked to share his late-in-life openness, which relieved him of tremendous guilt and psychological anguish. All my father’s siblings (two brothers and a sister) hid deep personal secrets throughout their adult lives, leaving them emotionally divided from each other. Maybe my father knew that his older brother was homosexual, but it was an unbroachable subject between them.

Finally, why would my uncle be so intolerant of his own brother? Was it just moral judgement? Or perhaps a deeper dysfunction, an inability to come to terms with his own sexuality, which was thoroughly mixed up in the extraordinary circumstances and regret of the 1957 crisis that cost him so much?

Not the man he might have been

I cannot find the truth of these things now. All the principle characters in the story are dead. I don’t wish to judge or lay blame. I can only mourn that my uncle’s true calling (one that would have utilized his intellectual gifts fully) was aborted so early in his career.

I wish I’d known him better. I feel sorrow that our respective political biases estranged us, after that initial promising visit to his Cavan farm.

I’m sad that my dad and uncle never reconciled, nor talked honestly about their respective pasts. And I wish that Arthur hadn’t died alone in a hospital corridor, with no family to share in his last days or moments.

All I can say for sure is that my uncle Arthur’s life was complex and contained deeply hidden secrets. Because of the Cold War, he was not the man he might have been, just like Herbert Norman.

• • • • •

Five great links on the Herbert Norman case

- “The Man Who Might Have Been: an inquiry into the life and death of Herbert Norman,” 1998, NFB documentary (watch it online here)

- Canadian ambassador jumps to his death in Egypt, 1957, CBC radio broadcast (listen here)

- Death of a Diplomat: Herbert Norman and the Cold War, an exhaustive website with documents, photos and interpretations for high school history students

- The Loyalties of E. Herbert Norman, Peyton Lyon, 1990 (download the PDF report that ultimately cleared Herbert Norman’s name)

- A 2007 commentary by Roger W. Bowen, drawing parallels between Norman’s persecution and the much more recent case of Maher Arar, who was betrayed by the Canadian RCMP to U.S. intelligence, who deported him to Syria, where he was imprisoned and tortured

Yeah

>

“Wheels within wheels.” A compelling piece, well researched and written. Thanks for sharing Art.

Oops thought I was on face book – the yeah comment was congrats on finishing and posting. I can see that if you were to write a book I’d lose you for a year, the process was so all encompassing. I am biased but you rare a great writer.

Yes, this is a wonderful story. I played Herbert in the NFB movie and all the same mysteries continue to haunt me. I was on the Wadi El Nil building of course, with it’s heady aroma of urine and feces festering in the early morning sun and as I rounded the top of the stairs into the sun rising over the Nile, I was blinded, as he would have been, it being the same time of day, and suddenly I was Norman, he was me, it was 1957, it was 1997, in that moment as together we stepped onto the roof there was a supernatural riveting of our natures. I never knew the man of course, but I could say that I loved him. In Japan I slept in his apartment in the Legation and in Ottawa I sat and talked with Irene who told me about his last kiss that fateful morning. I wanted a picture of myself but respected her privacy and didn’t impose but at the end of our meeting it was Irene who asked to have her picture taken with me. She said there was a family resemblance.

You have added a very beautiful and moving addition to the story; that of your uncle and father. Would there be a play in you about this? I thoroughly enjoyed the read. Thank you.

Keep in touch should the CIA ever release their documents.