The boy whose breath deserts him when he sleeps

It’s a busy Wednesday night at the Fergus swimming pool. Babies as young as a few month’s old are being introduced to the water in the small, warm pool.

Five-year-olds are swimming independently in the shallow end of the big pool, in that herky-jerky way of kids trying to figure out the mechanics of the front crawl. In the deep end, school-age children are practicing dives off the deck edge. Off to the side a tentative 12-year-old walks down the ramp entry to the big pool, followed by his teenaged instructor. He has short hair, bright blue eyes, and a noticeable scar at the point where his lower neck meets his chest. He stands in the water up to his mid-torso, then bobs his face briefly under the surface, but not deep enough to cover his entire head. But he pops up again quickly, wiping the unfamiliar water away from his eyes and face. His private swimming lesson continues, floating on his front with the aid of a pool noodle, walking until the water is up to his neck, and floating on his back for a few seconds with support from the instructor.

Kyle is nearly 13 years old, an engaging and obviously happy child, but this is his first swimming lesson ever, and only the second or third time he’s been in a pool in his life. From the time he was a newborn until just a few weeks ago, any open water, or blowing sand, or frigid cold temperatures, had been life-threatening for him, for a simple reason.

He had a tracheostomy – a breathing tube that poked out of his neck from the larynx. Pools were out of the question, because dipping the tube even momentarily below the surface would cause him to inhale water directly into his lungs. He would drown. Even bathing had to be closely monitored by his parents. He had never known the sensation of water washing fully over his face.

Why this radical and restrictive device? And why the sudden change that led to his first swimming lesson in early July of this year?

This is the story of Kyle Frappier, the boy whose breath deserts him when he sleeps.

• • • • •

I met Kyle’s father Chris Frappier quite by chance in early 2002. My wife saw him running by our house near Elora, and asked him if he was a marathoner, like me. “Yes!” he answered, surprised.

“Are you training for Boston?” she asked, craning her neck out of the car window.

“No, but I’m trying to qualify, and I hope to run the race next year.”

“My husband is running it this spring,” she said to Chris, then added, “you should run together!”

We did, and a friendship was born, especially on long weekend runs. Chris was six years younger than me, a little taller, and had a muscular upper body and close-cropped hair with a touch of grey at the temples. He was initially shy, but would suddenly reveal a wide grin with sparkling eyes and a wicked sense of humour when he spoke. The first time we went out together I asked Chris what he did for a living. “I’m a graphic designer,” came the reply, which stopped me in my tracks, because that’s what I’d been doing for the previous 15 years.

I did run the Boston marathon that year, travelling to the race with my wife and two sons, aged 13 and 8. And Chris qualified for the race that fall. By the time 2003 rolled around, we had already hatched a plan to drive down together in April. I’d show Chris the ropes of the historic road race and together we’d break three hours, a time we felt was within in our reach if we could run about 15 seconds faster per kilometre than ever before. That was the plan.

Race preparation with total strangers: Chris had no trouble finding female volunteers to write stuff on his body

But race day turned out to be too hot for two guys who’d trained through a bitter winter, a cold spring, and were wearing shorts for the first time that year. We stood waiting for the starter’s pistol with sweat dripping from our underarms. Chris had our intermediate split times written on his hand. I looked at him and asked, “Are we in for a surprise here?”

Within less than five kilometres the race turned miserable for me. My head felt like it would explode from the heat, and a blister was already growing on my right foot. Our sub-three pace was going to waste me before the half, I could tell. I told Chris to go ahead, asking that he wait at the chaotic finish line until I showed up. It was my fifth marathon, but my first real bonk, completely running out of energy at the symbolic “wall” of 20 miles. I ran a personal worst for the distance, at 3:30, and Chris fared only a little better, finishing about 10 minutes faster.

We collected our medals and hobbled back to our downtown B&B, 10 long blocks from the finish line on Boylston Street. When I took off my shoes and socks, Chris looked at the huge blister on my right foot and quipped, “You have six toes! You’re a freak!” I started laughing, and quickly forgot the misery of the previous four hours.

In the evening, we watched the elite race on Boston TV. The previous year’s winner Rodgers Rop of Kenya faltered on Heartbreak Hill (20 miles) and finished second to another Kenyan, Robert Cheruiyot. In a post-race interview, Rop explained his meltdown: “It was too hot.”

We looked at each other and started giggling. Then Chris said, “If it’s too hot for a Kenyan then what the heck are we doing here?”

The day after the race was cool, cloudy and drizzling – in other words, perfect running weather. “Really?” Chris asked as we went out for breakfast. Still, we were both happy to have completed the race and to be on our way home. We swapped life stories on the long drive back through upstate New York. And Chris told me that he and his wife Paula were expecting their second child, to go along with their three-year-old son Payton.

After a few weeks of recovery we resumed training, and set our sights on a fall marathon, the goal again, sub-three hours. Paula and Chris’s baby was due in mid-August. A newborn wouldn’t upset the apple cart too much. Chris was a driven sort of person. What he set out to accomplish, he always completed. When we met up halfway between our two homes for a run (we lived almost exactly 5K apart), he was always on time, to the minute. Before running, he had been a body builder. Then, improbably, he switched to broomball. Each time, he gave it his all. If you were Chris’s neighbour and you wanted to move some rocks for a landscaping project, Chris would surely help you. He was a rock as far as I could tell – constant, solid, reliable.

In his late 30s, Chris turned to running, and found near immediate success. He would be able to fit marathon training around the demands of a newborn, no problem.

• • • • •

Paula and Chris’s second baby was born at 1:22 pm on Thursday, Aug. 14, 2003. They already had a name picked out, because they knew he would be a boy: Kyle Evan Frappier. Their strong, pink, 7-pound, 3-ounce child was delivered at the Fergus hospital. “He was awake, alert, and perfect,” remembers Paula. She handed him to Chris, who gently rocked him, and soon he was asleep.

Paula and Chris’s second baby was born at 1:22 pm on Thursday, Aug. 14, 2003. They already had a name picked out, because they knew he would be a boy: Kyle Evan Frappier. Their strong, pink, 7-pound, 3-ounce child was delivered at the Fergus hospital. “He was awake, alert, and perfect,” remembers Paula. She handed him to Chris, who gently rocked him, and soon he was asleep.

Within minutes, the healthy newborn went from bright pink to deep blue, and Paula screamed for help. The maternity nurses scrambled, Chris handed over the baby, who promptly woke up and recovered his proper colour. The case baffled the hospital staff. They checked his airway and examined him for abnormalities. Nothing was obviously wrong with him. Chris left soon after to pick up Payton, who was at Paula’s workplace daycare in Guelph. He was worried as he drove back to the hospital, but was still expecting to introduce Payton to his new brother when they arrived.

However, as he walked towards Paula, he could tell something was seriously awry. She was crying, and the faces of the medical staff all told the same, solemn story. A fear suddenly crossed his mind: What if Kyle had died? How would he explain it to Payton?

Luckily, that wasn’t the case. The hospital staff in Fergus had concluded that whatever was up with Kyle was too serious for them to handle, because he continued to turn blue whenever he fell asleep. He would need to be intubated to assist his breathing – force-feeding him air while he slept.

Payton only saw his brother briefly, through the isolette window, as he was being sent to a waiting ambulance for transfer to Guelph. Paula had to stay at the Fergus hospital until she recovered from the drugs she’d been given to start labour, and Chris hastily made plans to take Payton to a neighbour’s house. Paula called her parents to tell them the new baby “wasn’t perfect” and also alerted a close cousin who was a pediatrician.

As the Frappier’s drama was unfolding, a far bigger calamity was occurring outside the hospital. At 4:10 pm that afternoon, around the time Kyle was being readied for transport, the largest blackout ever to hit North America touched Fergus. The hospital generators immediately kicked in, so it wasn’t apparent inside, but the whole of northeastern North America was thrown into pandemonium. Power failed in Toronto, and hundreds of thousands of commuters walked home on a sunny, summer afternoon. About 60 million people would soon be without power, in the US and Canada, 10 million of those in Ontario.

So as little Kyle was heading to Guelph, traffic lights were out, and the ambulance had to pick its way carefully into the city. After Paula was discharged, the couple headed down Highway 6 towards Guelph in the dark, not really understanding the crisis that was overtaking them.

The doctors at Guelph General Hospital were as confused by the newborn as the Fergus ones had been. One declared that he was a preemie (in fact, he was a full-term induction); another, who first saw him awake, said he looked just fine. (Paula said to him: “Read the chart!”)

Still, they supported his breathing by placing him in an isolette and administering oxygen, which prevented him from turning blue. They continued testing for the cause of the problem, even performing a spinal tap on the tiny baby, looking for infection. But as it turned out, Guelph also didn’t have the expertise to intubate a newborn.

“They were grasping at straws,” remembers Paula now. After two nights in Guelph, the hospital decided to send Kyle to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Hamilton Health Sciences, which is connected to McMaster University. The NICU (pronounced knee-Q) transfer team arrived to pick up Kyle and promptly snapped a polaroid of the baby and handed it to Paula and Chris – standard practice, in case the couple never saw him alive again. The little baby with the breathing disorder was now fully under the care, and control, of the medical system.

Once he reached Hamilton, Kyle was finally intubated, which allowed greater control over his ventilation. Instead of increasing his oxygen intake, the NICU could actually assist his breathing. They also gave him dozens of tests. They couldn’t name Kyle’s condition, but the problem was very apparent: for some reason, he failed to breathe normally whenever he fell asleep. But how and why that was occurring, no one could say for sure.

The NICU was caring for dozens of sick young babies, many of them premature births, however, Kyle’s case stuck out for a simple reason. When he was awake, he was a normal newborn, albeit one hooked up to several machines and covered in tubes. He was responsive, squirming and already showing an extroverted personality. The nurses encouraged contact, cuddling, cooing – everything you’d normally do with a baby. Kyle became the star of the NICU, a baby that was both normal and mortally threatened at the same time.

Paula did attempt to breastfeed Kyle, in Fergus, Guelph and then Hamilton, but it became increasingly difficult, because she was commuting back and forth, and the stress was also affecting her milk production. He soon became a bottle-fed baby.

Paula is a professional in the health care system, an occupational therapist specializing in care for Alzheimer’s patients. She a strong, outspoken woman with a full head of curly hair and a mother’s instinct to protect her child. As she remembers those early days in Hamilton, she voices a contradictory feeling: “They were doing an awesome job, but you lose control of your kid. If you’re not careful, and assertive, they’ll do anything they want, without even asking for your consent.”

After a week of tests, the NICU had narrowed the diagnosis of Kyle’s breathing disorder down to three possibilities:

- some sort of seizure problem

- a rare breathing condition known as CCHS

- a mytochondria-2 deficiency

Even if they couldn’t pinpoint the cause of the problem, they wanted to improve the way they were treating it, and move to a long-term solution. They approached Paula and Chris separately and floated the idea of taking Kyle into surgery to perform a tracheotomy, which would permit direct ventilation of the baby when he was asleep and freedom from a breathing tube down his throat. Chris resented their approach. He sensed a divide and conquer attempt to persuade the two of them to agree to what the medical team wanted, without fully explaining all its implications to the family.

After some discussion, Paula and Chris did agree to the surgery, and on his twelfth day of life, Kyle was wheeled into the operating room. His parents returned home to be with Payton. Together they cried, and began to wonder what their future as a family might be like. They also took the decision to give Kyle one more middle name, “Boston”, for the courage and endurance the little guy was already showing.

Paula dreaded returning to the NICU. They had been shown a doll with a plastic tracheostomy tube sticking out its neck. The device looked massive and horrible. But when she entered the room of Kyle Evan Boston Frappier, her gloom lifted immediately. His face and mouth, hidden for most of his life so far under the intubation equipment, was open and free. “I could see his perfect little lips!” she remembers now.

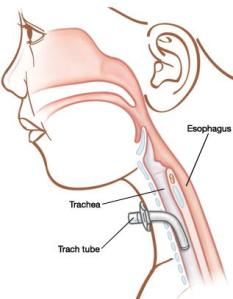

Tracheotomy is the operation that opens a hole in the airway by an incision between the second and third tracheal rings. The result is a tracheostomy, which includes the plastic device that is installed in the “stoma” (the hole), to which an external ventilator can be attached, or which could be capped off to allow normal breathing through his upper airway while Kyle was awake.

Around the time of the operation, the doctors in charge of Kyle were zeroing in on a diagnosis. They told Kyle’s parents that he was likely born with a rare condition called Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome, or CCHS. They had treated one newborn case previously, and were also handling a pair of older twins who had been born with it.

Here’s how Kyle explains it now, as a 12-year-old who’s been simplifying the complex medical condition to people all his life. “I breathe in air okay, all the time, but when I’m asleep I don’t breathe out enough, and the CO2 builds up in my lungs and bloodstream.”

He’s not at risk of suffocation, nor does he stop breathing completely while he sleeps. But the buildup of carbon dioxide stupefies him, and if left unchecked will progress from there to a coma. He could die in the night, or be injured irreparably. To put it another way, CCHS is a failure of automatic respiration; it’s an inability to breathe without conscious and voluntary action.

Like most people, Paula and Chris had never heard of the condition. “How rare is it?”, they asked the McMaster team treating Kyle. The reply shocked them. It went something like this: “There are likely only 500–1,000 cases worldwide and only a handful in Canada. And none of these kids are older than 25, due to the complications associated with artificial ventilation.”

It was hard to fathom. As the doctors explained it, the condition was caused by a single genetic mutation, which had recently been pinpointed to the PHOX2B gene. It meant that something was haywire deep in the most primitive, instinctive part of Kyle’s brain, the regulatory centre for breathing. Whether that deficiency was inherited, or simply a mutation that occurred while he was in utero, the doctors couldn’t say for sure, although in 90 percent of cases, the mutation was unique to the child.

This shocking news was followed by another prediction from the NICU staff: Kyle would likely spend his first 1–2 years in the hospital, so he could be monitored carefully, and hopefully grow out of the condition, as sometimes happens.

Paula and Chris were dumbfounded, but didn’t have time to ponder it very much. They were spending days and nights at the NICU, watching and learning as Kyle was successfully ventilated while sleeping, then disconnected from the machine when he was awake.

• • • • •

CCHS is a complex name. “Congenital” means that it is present from birth. “Central” refers to the fact that breathing is a brain-governed reflex. The “Hypo” part is the opposite of “hyper,” in other words, he is under-breathing. “Syndrome” hints at the fact that it’s not a disease; it was a permanent part of Kyle’s makeup, with no cure, only sophisticated treatment options to keep him alive every time he fell asleep.

But there’s a simpler term for the condition that comes from early European folk tales and a 1938 French play: “Ondine’s Curse.” Here’s how Kyle tells the story now.

“It’s about a prince who was dating a beautiful mermaid named Ondine,” he explains. (Kyle loves ancient civilisations and mythic stories; he first learned about Ondine’s Curse from a YouTube video.)

“But the prince cheated on the mermaid after she’d had a kid with him and had begun to lose her beauty. So, Ondine put a curse on him. During the day, he could be with his new love, and his breath would be his own. But at night, he would belong to Ondine, and she would steal his breath.”

Ondine’s Curse went something like this, according to another source:

You pledged faithfulness to me with your every waking breath and I accepted that pledge. So be it. For as long as you are awake, you shall breathe. But should you ever fall into sleep, that breath will desert you.

Kyle explains that the prince tried to stay awake to avoid his fate, but concludes, “Let’s be real – he probably died.”

And in fact, although CCHS had been identified in the early 1960s, that was probably the fate of most children born with the syndrome up until the 1980s. They likely died as infants, many never diagnosed because of its rarity, possibly of “crib death” or from the organ complications associated with oxygen deprivation.

• • • • •

Tracheotomy is an ancient procedure – the surgery was one of the first ever performed, possibly thousands of years ago. The first documented tracheotomy was in the 16th century by the Dutch anatomist Andreas Vesalius. The recent advances that made it a treatment for Kyle’s CCHS have been in artificial ventilation. A generation or two ago, a ventilator was a dishwasher-sized machine that only existed in the hospital. By the time Kyle was born in 2003, there were home models weighing only 30 pounds, for treating all different kinds of breathing disorders. And there were medical specialists called Respiratory Therapists who became very involved in Kyle’s care from a young age.

The tracheostomy was an ingenious solution to Kyle’s problem. It would allow him to breathe, eat, drink and make vocal sounds fairly normally, none of which was possible when he was intubated. (As he got older, it also provided a neat party trick that startled anyone watching him: he could drink a glass of milk at the same time as he breathed through the tracheostomy, an unnerving sight.)

The tracheostomy was an ingenious solution to Kyle’s problem. It would allow him to breathe, eat, drink and make vocal sounds fairly normally, none of which was possible when he was intubated. (As he got older, it also provided a neat party trick that startled anyone watching him: he could drink a glass of milk at the same time as he breathed through the tracheostomy, an unnerving sight.)

But it came at a cost. A complicated plastic trach tube had to be inserted into his stoma, and held there at all times by a collar encircling his neck. (Without it, the hole would begin to close naturally, within hours.) Not only that, it would take round-the-clock vigilance to care for the device. Several times per day and also at night someone would have to suction mucus out of the airway below the tube with a special machine; Kyle could never do that for himself.

Kyle’s trach (the short-form term is pronounced trake) also carried a special risk, referred to earlier. It was a direct entry into his airway, below the point where the throat divides into the esophagus and the trachea. We breathe through our mouths, but when we have a mouthful of liquid we reflexively swallow it into our esophagus, not down our airway. But if Kyle ever got water in his trach, it would be carried by gravity straight into his lungs. He would drown in fairly short order. Our cough reflex clears our throat; it doesn’t easily clear liquid that’s made its way into our trachea, as you know if you’ve ever inhaled water accidentally in the swimming pool.

Any sort of water would be a peril to Kyle: a swimming pool of course, but also a bath, a shower, even a garden hose squirted straight at his neck. There was no margin of error: if Kyle was submerged, even for a couple of seconds, he could perish.

Not only water was a risk. During the day Kyle had to breathe partly through the trach, and partly through his mouth or nose. The trach couldn’t be capped completely because the portion of the tube inside his trachea took up too much space; he needed to breathe partially through his upper airway and partially through the trach. So it was capped with a special filter, so he wouldn’t breathe dust or foreign objects directly into his lungs. A particular hazard was sand: because it’s not organic, even a few grains of it inhaled into his lungs could cause infection, and it would be there forever. That meant that beaches and sandboxes were as perilous for Kyle as pools and bathtubs.

At night, Kyle could sleep normally, as long as he was connected to the ventilator. It was a complex device, sensitively calibrated, with alarms that would go off if anything was wrong. It supplied Kyle with air from his surrounding room, not pure oxygen, and this had to be humidified by another machine attached to the ventilator, something that is normally done by our nose and upper airway.

Lastly, Kyle had to be attached to an oximeter at night, or when he napped during the day, as a failsafe monitor. If his oxygen levels dropped too low, it would sound an alarm so that someone would check the ventilator.

As Paula and Chris learned about all this technology in the days following Kyle’s tracheotomy, and watched it support his breathing at night, they began to see the shape of their future lives with their son: constant vigilance, complex machines, medical supplies for the trach, and sleepless nights for them on a scale that most sleep-deprived newborn parents could only imagine.

It was sobering. But they did have Kyle, and he was thriving. They couldn’t look too far ahead to the future, just yet. However, they began to ask when they could take their little boy home. In the hospital, Paula and Chris also began to push back, not accepting every test and procedure the medical team wanted. In his first month they refused a feeding tube for the newborn, a proposed colostomy, and the taking of blood gases (needle sticks) instead of the less invasive oximeter. They were asserting their right to some control over Kyle’s treatments, and declined tests they felt contained too much risk or were for improbable reasons.

• • • • •

Chris and I didn’t stop running together. A few days after Kyle was born, he called to explain what had happened. A couple of weeks later, after Kyle was settled in the NICU with his tracheostomy, Chris and I went out for a Sunday long run together. Mostly, I just listened as Chris explained the complicated story with this weird name I’d never heard before.

All the medical details aside, I could hear a lot of anxiety in Chris’s voice. He was near tears as we ran down a dirt road south of Fergus, sheltered from the summer heat by overhanging trees. He said he had dark thoughts, and felt guilty about that. He was starting to worry about his medical coverage from work, and if they would be able to care for Kyle at home.

And I knew from our trip to Boston a few months earlier that Chris had a difficult upbringing. His mother was alcoholic and had died four years earlier. His dad was a heavy smoker who “just didn’t deal with emotional stuff,” according to Chris. (He died shortly after Kyle turned one.) Chris was estranged from his sister, and his brother Aimé was a cocaine addict who had run out of second chances from his family. Aimé (“loved one”) had two, healthy young children, who Chris rarely saw. Paula and Chris, who’d done everything “right” during pregnancy, ended up with a second child that was in some ways, a bundle of joy, but also far, far from normal.

“Really?” Chris wondered. “I have to face this too?”

I couldn’t provide Chris with any answers. I scarcely understood the story, and had no experience to draw upon. I had no idea what I would do if I were in his position. I think I told him that I knew he was very strong, and that having doubts was no shame. Maybe I even used a marathon analogy: when you hit a bad patch in a race, you have to resist the urge to walk, and just keep running, confident that things will improve, somehow. “Just keep going,” I probably said, “even if the finish seems impossibly distant and the conditions are brutal. You’ve done that before. Remember Boston?”

• • • • •

Although the NICU staff said Kyle would be with them for a full year, Paula and Chris never accepted that verdict and took an immediate, assertive role in his care. Once his treatment plan was set, they began to ask “Why not?” to the question of caring for him at home, even as a very young baby. Kyle was severely medically fragile, not just a child with an inconvenient problem. But Paula and Chris believed they could handle it. They had complementary strengths: Paula understood the language of the medical team; Chris was excellent with the new technology that was supporting Kyle, and was a light sleeper who could be with his child a lot at night.

Even if they had misgivings, the NICU team began training the couple in every aspect of Kyle’s care they would need at home. How to change a trach tube. How to suction him out safely, a delicate procedure that risked stopping his heart. How to fill the humidifier pot and drain its hose without pouring the condensation accidentally back down the trach. How to read false alarms and reset the machine, how to recognize a true breathing crisis, and if necessary administer CPR to an infant.

Money was no small part of their worries. Chris had excellent medical coverage through his employer, a cardboard box manufacturer on Woodlawn Road in Guelph, for which he designed exterior labelling. The ventilators they’d need, two of them, were valued at $50,000 each, and would be loaned to them from a medical pool. Overnight nursing care, which they would eventually need so they didn’t have to stay awake all night every night of the week, would be covered by OHIP. But the consumable medical supplies for the tracheostomy would cost about $35,000 per year. Could they afford that? Would Chris’ insurance cover it?

They discovered an odd Catch-22. If they couldn’t afford the non-OHIP expenses for keeping Kyle at home, then he would be institutionalized, with the government paying for everything, a much more expensive proposition for them. It seemed nonsensical, but the spectre of losing Kyle, and having to “visit” him, was haunting to Paula and Chris.

By late September, Chris had returned to work, and was sorting out the insurance issues. Paula was on maternity leave, and Payton was back at daycare. Kyle was stable enough that a target date was set for his return home: Thanksgiving.

In fact, on the spectrum of CCHS, Kyle was definitely “light.” Some children with the disorder don’t even breathe properly during the day, and need round the clock ventilation. When Kyle fell asleep, sometimes his breathing problems didn’t occur for awhile, 30 minutes or more. The NICU team began waiting until his monitor showed low blood oxygen before connecting him to the ventilator. During the day, he was fine, and now past the newborn stage, he was awake more often.

And then Paula and Chris learned about a very strange coincidence, the chances of which seemed nearly impossible. Despite the extreme rareness of CCHS, the NICU staff knew soon after Kyle was born that there was another case of the syndrome, in their same small town of Fergus. In fact, there were two, because the case was a set of identical twins, both with CCHS. They had been born in eastern Ontario and had moved to Fergus long before Paula and Chris, to be near the specialized care at McMaster University. So, their proximity had nothing to do with the disorder, or environmental conditions, or anything like that. It was completely improbable, since there were only a small number of CCHS kids nationwide.

The twin girls were 17 years old when Kyle was born, just finishing high school. They offered to meet with the Frappiers and share their experiences. This was gold for Paula and Chris. The girls were supported by tracheostomy ventilation when they were young, followed by a pressurized mask device that ventilated them through the nose and mouth beginning at age eight (i.e. no tracheostomy). And they were about to transition once again, to a phrenic nerve implant, that would serve as an electronic breathing pacemaker by regulating the contraction of their diaphragm (i.e. no ventilator). They were a generation ahead of Kyle, and part of the first cohort that seemed likely to survive through to adulthood with CCHS.

Even if their form of the syndrome wasn’t identical to Kyle’s, it surely provided Paula and Chris with confidence that they could raise their child at home – especially if someone else in their town had managed the feat with two such children. And long-term, it offered the hope of solutions, transitions, and freedom from the risks and restrictions of the tracheostomy.

Finally, the day arrived to take Kyle home, just before Thanksgiving, as promised, two months to the day after he was born. They had to sign a form saying they wouldn’t sue the hospital if Kyle died, and then he was released into their care.

“At home, I have this perfect little baby room set up, just like everyone does,” says Paula, “and they bring in a truck load of equipment, the ventilator, a backup unit, backup batteries, all the suction equipment and trach supplies.” It was a visual reminder of how complicated their lives were about to become.

Paula drove home from Hamilton with a Respiratory Therapist from the hospital. They had a battery operated ventilator on hand in the van in case he fell asleep during the 45-minute drive. Chris was waiting at home with Payton.

The neighbourhood turned out to greet them, there was a sign on the house welcoming Kyle home, and Payton met his brother for the very first time.

“The day he came home was wonderful,” says Paula.

“Yes, it was a fabulous day,” remembers Chris. “It marked the true beginning for us as parents again.”

How far they had come in just two months.

Soon after, the twins came over to visit the Frappier house, and meet the baby with the same syndrome they had known all their lives. They held him, recognized the tracheostomy they had used for so long, and got him to smile, not a very difficult task.

• • • • •

But despite all their practice at the NICU, the transition to caring for Kyle at home was abrupt. There were plans for supplemental nursing care at night, government-funded, but initially, it was all up to Paula and Chris. She looked after the medical equipment and the arrangements for the private nursing that was to come, Chris handled the routine night care. He had more time off work after Kyle’s return home, but he was still shocked by how little sleep he was getting at night.

And at this point, our stories converge for a day, just five days after Kyle returned home. Chris honoured his plan to run the Toronto marathon with me, despite his tumultuous home life. He had been training through August and September, often late at night. It might sound crazy, but running was Chris’ escape, the only time he felt he had for himself. He later wrote about our Sunday long runs, “Art and I talked for hours on end. The miles flew by. I never wanted those long runs to end.”

So, on race morning he left his family behind, drove down to Toronto with me and my family, and lined up at Mel Lastman Square in North York to start the race. Although I knew Chris was under a lot of stress, I don’t think I appreciated his inner turmoil that morning. He later wrote:

“The night before the marathon I went to bed and tried to relax. Random thoughts and memories of the past months occupied my mind. But mostly guilt filled my heart. Kyle was a beautiful, happy baby boy. It did not take much to make him content. In the past week he had proven to me that he not only deserved to live but that he also deserved to be loved despite his condition and the challenges that came with it. I could not sleep, not a wink.”

Chris’ secret race plan was to rabbit for me, to establish a pace that would set me up for a sub-3 hour race, although he knew he didn’t have the rest or the emotional strength to handle the difficult last 10 kilometres himself. Remember: I didn’t know this. I assumed we were in it together. At one point about five kilometres in, I fell a couple of strides behind Chris. I never liked running behind him. His erect and confident stride was deflating, if you had any doubts about your own ability to hold a tough pace. I quickly pulled even, and made sure I stayed there.

We passed the halfway point in about 1:31 – a tad slow, but with a sub-3 finish possible if we could speed up a little in the second half. As we approached the spot where I had arranged to see my wife, the corner of Spadina and St. Clair, Chris was lagging behind me. He says now: “I was emotionally spent and unravelling fast.” I saw my family, and leapt in the air with a fist pump. When I landed, one of my calves cramped suddenly. I stopped for a quick hello, and then started moving forward again, albeit slowly.

I never saw Chris after that. He apparently collapsed in Nichola’s arms, in tears, hurting from a pain that was greater than just hitting the wall in a marathon. I dodged my cramp, accelerated gradually, and was on pace again within a kilometre or two. But I could not make up the time we’d lost in the first half. I finished in 3:04, shed a few tears of my own, and took up a post at the finish line to wait for Chris. He eventually limped in 20 minutes later, suffering from severe leg cramps.

He had written “KYLE” in black letters on his left leg, and people yelled the name throughout the race. “Go, Kyle!” That made Chris smile. But it wasn’t so good as he hobbled up University Avenue in the last few kilometres, sometimes walking through intersections where police halted cars to let him pass.

“Come on, get running Kyle!” they yelled. Chris was joking about that only minutes after the dreadful race – in his typical, self-deprecating fashion. He later admitted that running a marathon only five days after bringing your vulnerable newborn home from two months in the hospital probably wasn’t the brightest idea after all. If hurting himself was meant to resolve his inner anguish, it wasn’t so good for that either.

• • • • •

The next couple of years were difficult ones for Chris, although he was parenting successfully as far as I could tell. He and Paula got their first night-time nurses in December 2003, three nights per week, and moved Kyle from their upstairs level to a room downstairs where the nurses could observe him without waking his parents. The nurses were hired through private agencies, but paid for by government funding, funnelled through the local Community Care Access Centre (CCAC).

In theory, Paula and Chris had nursing care during the week, allowing them to sleep uninterrupted. But in practice, it was difficult to find all the nurses required. A few worked with Kyle for many years, but others stayed a single night and never returned. Some arrived trained, others were not. One night a nurse dislodged the trach tube, and tried to force it back improperly, injuring Kyle, then screamed. Chris flew downstairs fearing the worst, but instead had to attend the problem, wipe blood off Kyle’s neck, and then send the nurse home.

Every night, before the nurses arrived, Chris would put Kyle to sleep, and hook him up to the ventilator. And each night he wondered, would Kyle be alive in the morning? Then, when he went to bed, he often found Paula crying, sometimes in her sleep.

By day, he went to work, but he would have to leave at lunch and go take a nap in his truck. He was functioning, but at a very utilitarian level. He was going through the motions, but caught up in worries about money, the future, and even whether he could keep his job and what would happen if he lost it.

After nearly a year at home, Paula’s maternity leave was up, and she wanted Kyle to go to the daycare at her workplace, Homewood, where she worked as an occupational therapist. It was all part of their general philosophy regarding their toddler. They wanted him out in the world, not protected in a bubble.

But the move was initially opposed by the specialists at McMaster, who were still actively caring for Kyle, with regular appointments. Paula says the hospital threatened to call Family and Children’s Services in Guelph if the Frappiers followed through on their plan to send Kyle to daycare. “It was like Kyle wasn’t entirely ours!” she says now.

Nonetheless, the couple persisted, and eventually got training for the Early Childhood Educators at the daycare in the procedures for suctioning Kyle, hooking up his ventilator, and, in an emergency, replacing his tracheostomy tube. They were examined by a nurse from McMaster who had been caring for Kyle since his earliest days, and passed with flying colours.

Sometimes, Paula would take Kyle to the workplace daycare with her, but on days when she was on the road, or working from home, Chris took him to daycare in the mornings before driving across town to his own job. Here’s how he described the routine of getting him in the door: “I had the ventilator in a duffle bag, that weighed 25 pounds, the suction machine was another 15–20 pounds, our ‘go’ bag with spare trach parts, an ambu-bag, a diaper bag, and of course Kyle himself. I only wanted to make one trip so I had it all over my shoulders and Kyle in my arms.” Whew. Good thing Chris had trained as a weightlifter all those years before.

Paula and Chris say that caring for Kyle changed many lives at Homewood’s Workside daycare. It brought out the best in the caregivers, and some of them went on to get further professional training in CPR-related fields. Kyle was a charmer, and a rascal. Once at naptime, he went down, pretended to be sleeping, and when his caregiver bent down to hook up his vent, he opened his eyes and said “BOOO!”, scaring her silly, but providing a great story that Chris still recounts with a grin.

I don’t think there’s much that’s “natural” about parenting. You bring your own strengths as a person, but also your weaknesses, sometimes as a result of the way you were raised, or because of other problems you encounter in life. Then you make it up as you go along. You improvise, make mistakes, learn, and grow. It never stops really.

Chris figures it took him a long time, as much as two-and-a-half years, to fully adjust to the shock of having Kyle and learning to care for him, not just mechanically, but as a full loving parent.

Kyle’s voice was different, because the tracheostomy changed how air passed over his vocal chords, and also prevented him from properly hearing his own voice. “I would be driving home in the car, Kyle would be chatting away, and I couldn’t understand him,” says Chris. He would stop the car and cry sometimes, then return home and try to hide his disappointment from Paula.

One day, he walked in the door with a blank look on his face and Paula glared at him. Then she announced sharply:

“We can’t change the way things are, but you can change your attitude. I hope you’ll join us in our journey, but we’re moving on, with or without you!”

Chris went to their downstairs bathroom and looked at himself in the mirror, and at a photo of Walter Payton, the NFL running back he greatly admired and who his first-born son is named after. He thought, that’s it, I have to be better, and stop worrying about things that haven’t happened and may never happen. He pulled off his blank-stare mask, and symbolically flushed it down the toilet.

He also made up a grace that he would try to repeat every day, his three touchstones:

“I’m grateful that I’m alive. I’m grateful that Kyle made it through the night. And I’m grateful that Paula and Payton support me.”

Things improved from there for Chris. How does a runner measure improvement? With race results of course! In 2006 he ran his best marathon ever, drawing on all the strength he’d gained in learning to parent Kyle, an even-split 1:33/1:33 (very rare) for a 3:06 finish. He also set personal bests in all his other race distances, the 5K, 10K and half-marathon.

But more importantly, he became a better husband and father. He developed a bedtime ritual with Kyle. Every night he would hook him up to the vent, sing him songs, and Kyle would look back and laugh at him. “We became very close,” says Chris.

This is all from Chris’s point of view. When I ask Paula about it separately, she won’t talk about his meltdown or confirm her role in his recovery. Instead, she talks about her own doubts, insecurities and challenges. I guess the truth lies somewhere in the middle. Their coming to terms with a radically changed life is likely a lot more complicated than I’ve described here.

• • • • •

When Kyle reached school age, his parents faced a new problem. Although he wasn’t napping any more, his tracheostomy still needed special care, and the school board didn’t want to take responsibility for him in the same way the daycare had been willing to. In fact, they had a rule that any child with a tracheostomy had to be accompanied by a nurse.

Before he could attend kindergarten the CCAC had to find more nurses, who would accompany Kyle to school, sit near him, and watch over him throughout the day. If a problem arose with his trach tube, the nurse would handle it, not a teacher.

This continued for eight years, until just a month ago, although as Kyle got older the nurse presence grew more discrete. Eventually, they were present in the school, but not in Kyle’s classroom.

You might think that other children would tease or perhaps even bully the young kid with the plastic tube in his neck. Not so, maintains Paula, Kyle, and his brother Payton. “I don’t think he was ever teased,” says Payton, now 16 and about to enter Grade 12. If other kids ever asked about the thing in his neck, Kyle would tell them simply, “I need that or I’ll die.” That put an end to the speculation pretty quickly.

Once, Kyle and Payton were rough-housing at home, and Payton knocked the tracheostomy out of Kyle’s neck. Both parents were home, so the five-year-old Payton was sent to his room while his parents worked to replace the tube. “That’s the first time I realized I couldn’t do some of the things that brothers do,” says Payton.

But his parents did try to do as many regular things as possible. Early on, they figured out how to be mobile, even if it meant lugging a ton of equipment everywhere. They bought a minivan. And later, they got an RV trailer, so they could go camping together but still be next to a power outlet at night.

“We haven’t stopped Kyle from anything but the real life-threatening stuff,” says Paula. He took part in karate and soccer. (He had to wear a special neck protector like a hockey goalie wears, when he was sparing with other kids, to shield his trach.)

They tell a hilarious and complicated story about their first trip to Disney World in Florida, when Kyle was six. It required that all their equipment be pre-approved before their flight, and even then, the pilot asked to examine it before takeoff, because he had the right to refuse to fly if he felt it would interfere in any way with the aircraft controls.

Once there, they were strolling the grounds, and promptly ran into another child in a stroller with a tracheostomy in his neck. They questioned the parents, and learned the other child had CCHS as well. Small world. They compared notes, and came away greatly relieved that they live in Canada, with most of the extra costs of raising Kyle covered by public health insurance.

Eventually, Paula and Chris came to regard Kyle’s extra care as if they were running their own small business, with a division of labour between them. Paula handled equipment maintenance, communication with the medical system, and human resources (the night nurses). Chris was in charge of transportation, accounting and administration (he maintains a complicated system of “Kyle’s Files”) and nighttime alarms. It took years, but they adapted as a “team” to the new normal, which very few people outside the medical system truly understood.

“I don’t talk about it much, I definitely don’t lead with the fact that I have a kid who needs such specialized care,” says Paula now.

• • • • •

Before Kyle turned one, he was tested to determine the genetic basis of his condition. A blood sample was taken and sent to Germany. A muscle biopsy went to California. And the verdict came back: he had CCHS and it likely occurred as a spontaneous mutation.

Paula and Chris could have been tested as well, to see if either of them carried the mutation, albeit without symptoms. They decided not to, because they didn’t want to face the chance that one of them might feel responsible for Kyle’s condition. It could disrupt their solidarity. Payton has also not been tested, although some day they (or he) might want to, should he decide to have kids, as he might also be carrying the CCHS genetic mutation.

Kyle’s parents are sanguine about his condition now, a far cry from how things were a dozen years ago. “I saw 30 kids and 30 families that were in far worse situations than us, back during our time in the NICU,” says Paula. “It was an revelation to realize that God isn’t a genie who makes everything better.” She says that before having Kyle she was often judgemental of others, but now, not so much. “You never know what other people are going through,” she says matter-of-factly.

Chris says that although Kyle is still vulnerable and will face challenges all his life, he believes that by the time he’s 25 or 30 years of age (like the twins are now), “they will have invented something internal to regulate his breathing, and he’ll be able to live independently, without night monitoring.” Chris isn’t referring to the phrenic nerve implants the twins have, which he and Paula believe carry an unacceptable risk of failure or disability. He thinks there will be something new that will help all kinds of people with breathing problems, like quadriplegics and others.

• • • • •

When Kyle was eight, he went to McMaster to see if he could be ventilated through an external mask at night, rather than via his trach, like the twins did. He tried it for one night, and then announced to his parents: “I don’t like it. I’m happy with my trach.” Chris actually tried the mask himself, and said it was scary, providing a blast of air that he didn’t think he could sleep with.

I had lunch with Chris around this time, and he couldn’t hide his disappointment. (I had moved to Guelph, and no longer ran regularly with him.) The work and the routines surrounding the tracheostomy were still enormous. The prospect that it would continue for years more was hard.

Then, by chance last fall, two things came together. Kyle realized that he would be entering high school soon, and he didn’t want a nurse trailing around after him at school any more. He also wanted to learn to swim and be able to enjoy the water, and the beach.

At the same time, McMaster informed them that new ventilation technology was available, with a simpler, smaller mask. It took awhile for them to clear a non-emergency time at the hospital when Kyle could use it for a week under close supervision. The stars aligned this past June, and the three of them went down to try. Chris had a strong hunch that this time, the new system would work, and Kyle would accept it.

At the same time, McMaster informed them that new ventilation technology was available, with a simpler, smaller mask. It took awhile for them to clear a non-emergency time at the hospital when Kyle could use it for a week under close supervision. The stars aligned this past June, and the three of them went down to try. Chris had a strong hunch that this time, the new system would work, and Kyle would accept it.

Paula removed his trach and the medical team covered his hole with a temporary patch to keep it open. Kyle went through his first night using the new mask and ventilator without any issues. After three days of further tests and monitoring things were clear to suture up the stoma for good, after almost 13 years with the live-saving but highly problematic hole.

Chris sent me a text with a photo of Kyle last June 6, post-surgery.

“What?” I replied. “Goodbye trach?”

“Yes,” pinged the instant reply. “We are on top of the world!”

Chris hardly slept during the nights in Hamilton, he was so confident in the outcome. And when he got home, with the remainder of the week off work, he went on a manic shopping spree. He and Kyle were passing the “rock farm” south of Fergus (landscape supplies) and he spontaneously drove in. Kyle looked at some volcanic rocks and observed, “It’s like a new beginning! And volcanoes create new landscapes!”

The metaphoric observation from his soon-to-be teenager stunned Chris. He spontaneously bought a pile of the black rocks and loaded them into the back of his truck. He and Kyle plan to use them for some sort of project together.

I visit Fergus in early July, and see Kyle, Paula and Chris for the first time in years. I watch with them as Kyle takes his first swimming lesson. Afterwards, we go over to their house for what I expect will be an hour-long interview. But it stretches to nearly three hours, sitting outside until the mosquitos get too bad, then moving inside to the lower-level family room, next to where Kyle still sleeps in a small bedroom.

They describe Kyle’s first days in a flood of memories, interrupting each other constantly, interjecting, anxious to tell their story, especially now that it seems to have such a happy ending. Kyle constantly adds humorous asides, like, “I had a feeling in Hamilton that they were happier than me!” (Payton is at work in Elora, and isn’t part of the interview, although I talk to him later on the phone.)

At about 10:30, they put Kyle to bed. It’s the first time I’ve ever watched the routine that I’ve heard about for so long, only with the new technology this time. The ventilator sits beside Kyle’s bed on a stand, about the size of a hospital vital signs monitor, and with a ton of lights and numbers. Kyle dons his new mask by himself. It looks a little like the early hockey goalie masks, a plastic device that covers his nose, with Velcro straps around his head to hold it in place. He smiles underneath the mask, and his eyes gleam. He says goodnight to his parents, and rolls over. I expect he’ll be asleep in minutes.

Chris pulls the sheet away from Kyle’s lower body and tapes the oximeter sensor to the outside of his right foot. It takes only a few seconds of efficient, well-practiced motion. Then they turn out the lights and wish Kyle good night.

Twenty minutes later, the night nurse arrives, Selena, who has been coming to look after Kyle at night since he was four. Her job is lessened now. She has reading and crafts to keep her occupied, and she will check on him every hour, but no tracheostomy care is necessary, and the alarms are less frequent with the new ventilator.

Paula and Chris want to eliminate the night nurses altogether; they feel they can handle it themselves now. But they’re going slowly, so as not to alarm the staff at McMaster. They’re down to four nights per week. By year’s end, they think it will be none.

Kyle is classified by the medical system as MFTD – “medically fragile, technology dependent.” Chris says that Kyle’s life will always have restrictions, but that he’s always taken them in stride. And in the final analysis, “when he goes to bed at night, he is confident that he’s in good hands.”

Paula adds, “We love him to bits and we wouldn’t change a thing now – he’s been so amazing for us all.”

Thanks to Paula, Chris, Payton and Kyle for sharing their intimate stories with me, and for most of the photos displayed here as well.

amazing story Art

>

“Amazing” was exactly what I was thinking as the story was drawing to an end. It read like a good book that I didn’t want to put down. Often we do not realize what challenges other families face with grace and perseverence.

I have had the pleasure of knowing the Frappier family for a good 8 years now, through karate. I am privileged to be the head instructor of the karate school that Payton and Kyle trained at. I took an immediate liking to the kind and thoughtful young boy that was then Payton. Upon meeting Kyle a short while later, I immediately fell for the blonde haired, bright blue eyed sunshine with a trach. I quickly became interested in his story, as I had grown up in school with “the twins” mentioned in this story. I learned of his story, though not quite as in depth as this blog lays it out. This gives a great in depth view (though I know we can never know everything they went through) of their lives before I knew them. We have been very close in the past years through the karate school, where I have contributed (in small part) to guiding the boys to success in the martial arts. I am incredibly proud of these 2 young gentleman for their accomplishments in and out of the dojo, and was elated to hear of their exciting new life sans trach. I’ve experienced Chris’ near tears as he spoke of his sons volcanic metaphor, the excitement in Paula’s voice as she describes all of the fun things he’ll be able to do now, and the giant grin that stretches across Kyle’s face whenever I ask him about it all.

The boys are getting older, moving on with their lives and are frequenting the dojo less and less, and I’m going to miss their dedication greatly.

Thanks for taking the time to interview the family, and put their amazing story of overcoming obstacles out there to inspire others.

Certainly this is a life changing epic story story of courage and love by parents faced with with their lives shockingly redirected by an unlikely errant gene. I honor them for their selfless devotion to their unfortunate child.

Such a beautiful, epic, emotional story! Tough to read at times through the tears clouding my vision, from feeling their challenges, triumphs and heartbreaks. The strength, courage and love that this family found to perservere is inspiring and undeniable!

Chris is my oldest brother. Although I wasn’t a part of their struggles, I can envision my brother’s strength and courage to make it through this challenge. He has always been my hero for being the person I would most like to be like. Having Kyle in my life now is a blessing from God. I am forever grateful to have Chris and his amazing family in my life. I love you guys!